15 December 2015 (revised 10 June 2016, 6 August 2017, 6 May 2019, 12 October 2019, 10 November 2019, 20 November 2019, 8 March 2022, 5 December 2023, 18 December 2023)

See Mans influence on Chobham Common 231218 for sources, references, etc

Looking at Chobham Common, be it walking, with dogs or horse riding, the vegetation is the obvious scenery on the Common. Naturally, Surrey Wildlife Trust – through Rangers and volunteers – is conserving the landscape in to its natural, heathland ecology. But what of the terrain itself? Man has had a major impact, whether we are able to see it today or not, on the landscape of Chobham Common and its history.

Obvious features can be traced to pre-history – barrows , etc – and medieval times – enclosures (eg Bee Garden , Fishpool , Glover’s Pond, and Gracious Pond, before it was drained (but still leaves a significant feature on the landscape). However, there are four more recent events which have shaped how we see Chobham Common today; figure 1 plots some of the events.

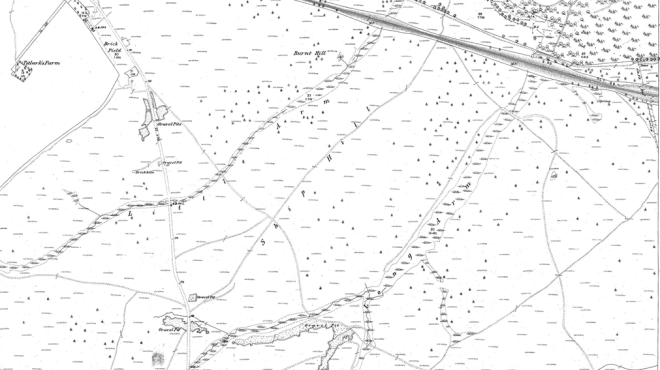

Figure 1 Man-made features plotted on a 1948 air photograph

(Green dots = bomb craters; orange lines = WWI trenches; olive lines = roads altered as result of M3; solid black lines = oil and gas pipelines; blue = Gracious Pond; red = Great Camp of 1853; PoW Camp to the south of text “Chobham Common”)

1853

First, although its impact will have been diluted over the years, is the Chobham Common Great Camp of 1853. The Surrey Heath Local History Club has published Chobham Common Great Camp 1853 recounting the ‘content’ and progress of the Exercise. Suffice, “…apart from being an impressive display in its own right and contributing to the success of the British and French in the Crimean War, it was undoubtedly an enabling factor in establishing Aldershot as the home of the British Army and spreading War Department properties across the Surrey/Hampshire border.” The divisional “Camp of Exercise” an experiment, proposed by the Duke of Wellington before his death, had never been tried in peace time before. “Hitherto there had been nowhere in the United Kingdom, except near Dublin, where sufficient men could be collected together for the manoeuvring of even a single brigade”. Operations started on 21 June and until 20 August 1853 when the ‘camp’ broke up, a variety of military displays were put on to large gatherings by a force:

comprising four regiments of cavalry, three battalions of Guards, two brigades of infantry, each comprising three regiments, one troop of Royal Horse Artillery, three batteries of Horse Artillery, a company of Sappers, and a Pontoon train

It is said there were, in two batches, 8,000 men and 1,500 horses. To prepare the ground for the Camp, the forerunners of the Royal Engineers (Royal Sappers and Miners) were busy on:

…The Common where the encampment was formed was an extensive tract of waste, varied with hill and dale. The amplitude of the district, its freedom from enclosures, from wood or bush, or from barriers or hedges to mark the boundaries of individual or corporate properties, and its succession of swelling heights, well adapted it for the purposes of an instructional encampment…

The contingent of Sappers divided: one detachment was tented south of the ‘Magnet’ (the HQ site and believed to be Flagstaff Hill – see 1871 1:2,500 Ordnance Survey map and Wyld’s plan (fig 2) and that a “…flagstaff was erected yesterday on “Magnet-hill” the soubriquet given to the head-quarters on the encampment…” (see fig 3 as a perspective from ‘The Magnet’): another, on 20 June 1853, was detailed to support the team building the pontoon to be built on Virginia Water. By 22 June 1853, the Sapper force consisted of 297 all ranks . The initial detachment was camped firstly “…on the skirts of Colonel Challoner’s wood, then on Sheep’s-Hill [now Ship Hill], and lastly on the Oystershell-hill near the “Magnet” [sic]…”

The Sappers had a number of tasks including setting out the boundaries of the regiments in the Camp on a large-scale plan “…Corporal Sinnett [*]drew the 12-inch plan furnished for the use of Colonel Vicars [**]…”. The whole area was also surveyed and drawn at 2 inches to a mile, and Aldershot Heath surveyed and plotted at 6 inches to a mile. It is likely that Figure 4, dated 1855, was based on the former ***.

* Valentine SINNETT, Service number 2152, 16th Survey Company, Royal Engineers, b. 1830 , Letterkenny, Donegal, Ireland, d. Q2 1865, South Stoneham District, Hampshire. Corporal in 1861. (Source: www.ancenstry.co.uk)

** Edward VICARS, , in command of the contingent of Royal Sappers and Miners at the Camp, b. 22 May 1797, Dublin, d. 8 Sep 1864, St Leonard’s on Sea. He retired as Major-General in January 1855. (Source: www.ancenstry.co.uk)

*** British Library reference Maps 2560.(24.).

Then they started works that could impact on the landscape:

…springs and watercourses were sought for and collected into small reservoirs or basins, at sites convenient for access as practicable. In some places small trenches were excavated, to afford easy channels for conveying the water to the terraces. These tanks were for domestic uses. Attached to them were larger ones for washing purposes, which were filled by the surplus water from the drinking reservoirs through the agency of small troughs, fixed near the top of the partitional embankments. Where springs could not be found in sufficient numbers, wells were sunk to afford water for the troops…In several instances the men were interrupted in the service by the presence of moving quicksands…To keep the ground from being undermined by the sand, rough sap rollers were at first constructed and sunk, but as there were found inadequate to meet the difficulty, on account of the sand oozing through the interstices of the brushwood, some barrels were securely fixed at the bottom, which at once offered an effectual resistance of good clean water. Into several of the wells two or three bushels of pebbles and shells were thrown to purify the water in its infiltration…Two artesian wells were also bored late in July, one to a depth of sixty feet and the other to thirty-five feet…

Figure 2 Extract from Map of the encampment on Chobham Common…

Figure 3. The military review – the camp at Chobham. The troops returning to their encampment after a field-day, 1853 (Coloured tinted lithograph by Edmund Walker after Louis Haghe (1806-1885), published by Ackermann and Co, 8 October 1853.)

[Believed to be looking north-west from ‘The Magnet’ with Staples Hill to the left]

(Source: National Army Museum, Image number: 8093, http://www.nam.ac.uk/online-collection/detail.php?acc=1968-06-295-1 )

Figure 4 Extract from Country around Aldershot and Chobham, original at scale 4 inches to one mile

Streams and brooks, draining into Virginia Water, were dammed, some 10-15 feet wide constructed from fir poles and faced with sods and filled with soil: “…in this way two or three fine expansive sheets of water were formed…One sheet was behind the cavalry stabling on Egham Common, and others, named “The Great Arm” and “The Little Arm”, were at the base of Black-hill and of Sheep’s-hill [now Ship Hill]…” (see fig 5). The Sappers then turned their attention to the building of the camp kitchen; the sides of the flue arrangement were “…built up with sods to a height of fourteen inches…A trench was dug round the kitchen from which at one end rose, to the height of above six feet, a mud stack containing two distinct chimneys shaped into ornamental pots. At the other end, the two fires were lighted…” . They were called on to a variety of the tasks:

They repaired and adapted the poor-house at Burrow Hill for a general hospital; erected a flag-staff for displaying the royal standard; enclosed a large area of ground with a canvas wall seven feet height, within which were pitched marquees and different tented conveniences for the use of the Queen and Her Majesty’s Consort and guests; and watched and managed the tent-ropes of the royal pavilion, &c, within the compound. Here likewise they erected a cookhouse of brick, after the form of their own kitchen, and cut a road about two miles long, from Colonel Challoner’s plantation to the “Magnet”, as a carriage drive for Her Majesty. The road led across one of the artificial sheets of water…It was called the “Queen’s Road”, and the dam across the sheet of water was dignified with the name of the “Queen’s Bridge”…”

Probably, more significant for the Chobham Common landscape, the Sappers were then directed towards the fortifications:

To give an additional warlike feature to the evolutions of the division, some temporary fieldworks were thrown up. These consisted of three redoubts, two irregular, with faces of very unequal length, on Oystershell and Catton Hills, and one regular, on Sheep’s-hill. The one of Oystershell-hill was revetted on one of its faces with brushwood and fir-brushes woven upon pickets, while its remaining sides were cased with sods. The other redoubts were revetted wholly with sods. Sheep’s-hill redoubt was a square work, with two platforms for one field-piece each, and its sides in the interior were each sixty feet long. Four shafts of six feet deep were sunk under is right face, and the charges, in boxes containing 100 lbs. of the gunpowder, were laid and tamped ready for explosion on the 6th August…

The History records that the field works were completed in early August. The Spectator recorded that on “…Wednesday the Sappers began to throw up a redoubt with entrenchments on the Windsor road; which were partially used next day, when the Queen was present” . Queen Victoria (on occasion with Prince Albert) visited the Camp on 21 June , 5 July, 4 August and 6 August 1853. Unfortunately for the latter visit the plans to explode the mines planted on Sheep’s-hill failed using charge from voltaic batteries, instead they were detonated “…the ordinary way the powder-hose to form the train…” .

Although it is not recorded who constructed them, shallow ponds were prepared in the peaty soil of the Common for watering the cavalry horses .

It is perhaps not remarkable that the commanding officers of cavalry regiments accustomed to the convenience of a barrack – indeed as they had never been in camp it is not strange that it was so – protested [fearing that the horses] would get bogged down and drowned [wrote Sir Evelyn WOOD]. The Assistant Quartermaster General…went up to General Lord Seaton, who was in command of the camp of exercise, and said: “My Lord, will you order them to ride alongside of me, and we will gallop through every pond?”. “The order was given…and executed, to the great detriment of the officers’ tunic, for in those days full dress was worn in camp.”

As a footnote to the 1853 Great Camp, and a demonstration how events can have a lasting influence is the ‘Treacle Mine’ affair. There had always been gossip in the Chobham area of a ‘Treacle Seam’ and the story goes that a patrol leader and a friend Boy Scout from the 3rd Chobham Troop started tracking a trickle of oozing, sticky substance (the story also goes on that they discovered the patrol leader’s sister ‘in a compromising situation’!) . The truth is that for the Great Camp :

…large quantities of provisions were stored there, including 30 hogsheads (barrels) each containing 56 gallons of molasses which were used, in the main, for horse fodder. To keep the barrels cool and prevent fermentation, a shallow excavation was dug out of a small hillock known as ‘The Clump’ and the barrels were stored under a thin layer of soil….When the troops departed, the barrels were left and they remained buried until 1901 when they burst and the contents started to run down the hillside.

One version is that ‘Treacle Mine’ had been excavated in Chobham by 1904. Some of the residents thought it was a redevelopment of the manufacture of gunpowder and that the miners were looking for fuller’s earth. When whole fields were used for the cultivation of lavender, it was often said “something smells round here!”. Another version is that later in the 1930s a local person discovered a spot on the Common where there was large quantities of treacle welling to the surface. Within a few days, scores of them were coming to dig deep pits, into which the treacle oozed, and could be scooped up by the bucket-full ; “…when some of the enthusiastic locals dug their pits deeper and struck something – well several somethings – in fact hundreds of giant wooden barrels of mollasis [sic]. These had been there for some years, and the wood had started to fall appart [sic] and let the contents ooze out” . Was this at the same site or a different site, or two different versions of a story with an underlying element of fact, and what effect did all this digging have on the landscape?

In 1855 an Inclosure Award was made by Parliament of part of Chobham Common to Arthur George ONSLOW, 3rd Earl of Onslow (b. 25 October 1777- d. October 1870) outright, the rest comprising several thousand acres of common land was uninclosed but associated with his land. ONSLOW derived his title to the Manor of Chobham from Walter Abel who had been granted it by George II for a term of 1000 years. When ONSLOW took over the title it then comprised 2,658 acres of arable land and 1,672 acres of grassland; Chobham “Waste” or Common formed part of this lease. Previously, in 1832, the Chobham Commons Preservation Committee had been set up to protect the rights and interests of parishioners over the vast tracts of common land surrounding the village. (Leaping ahead chronologically, the Common was purchased in 1968 by Surrey County Council from the then Lord ONSLOW for £1 an acre).

1871-1900

The next significant event was the Autumn Manoeuvres of September 1871. Held over a wide area, from Aldershot to Chobham, these were held in response (like the Great Camp) to increasing concerns that the British Army was ill-prepared to tackle their adversaries, especially their modernising of battle tactics. However, unlike the 1853 Great Camp – a standing camp – these were to be mobile engagements; “…most commentators agreed…that the 1871 manoeuvres marked Britain’s coming of age as a modern military nation.” The order for the Manoeuvres was issued at Aldershot on 13 September 1871 :

The Manoeuvre held until 23 September 1871 consisted of a series of mock battles, choreographed by General Orders (see ) with the First, Second and Third Divisions held in an area defined by the Military Manoeuvres Act, although in reality area used was much wider (fig 6). The battles were widely and comprehensively reported in the press at the time; for example, the Battle of Chobham on 20 September , and the Battle of Foxhill reported on 22 September . As The Spectator of 23 September 1871 records of the Exercise: Eight days ago the 1st Division, 10,000 strong, under Sir Hope Grant, and representing the British Army, was attacked by the 2nd (Carey) and the 3rd (Staveley)… These two were, one to carry the Hog’s Back, the other to turn it by Aldershot, and drive the British to Chobham. Sir Hope Grant, however, refusing to hold the Hog’s Back, retreated to Gravel Pit Hill, above Ash, and seducing Staveley to follow him, routed that General before Carey’s wide sweep to the westward could take effect. Nevertheless, Grant, as pre-arranged, retired by Pirbright to Bisley, on the north of the Basingstoke Canal and South-Western Railway. On Monday, the two divisions again assailed the first, Staveley crossing the canal, and Carey working round by Frimley and Bagshot. The overwhelming force directed against him compelled Grant once more to yield, and he fell back into an entrenched camp, the apex of which was Staples Hill, the right flank

Figure 5 Extract from 1871 Ordnance Survey 1:2,500 map showing “Little Arm” (north of the Memorial) and “Long Arm” (cf “Great Arm”) to the south

Figure 6 Extract from “The Autumn Campaign: Plan of the Country Around Aldershot”

towards the railway at Sunningdale, the left over Gracious Pond, all marked in Wyld’s map [see below]. On Tuesday the two divisions made a fruitless attack on the guns, redoubts, and rifle-pits, and were, of course, repulsed. So far, the sole use of the manoeuvres had been to test the tactical management of troops and their marching capabilities, to test also “the Control,” and exercise infantry and cavalry in outpost work and scouting.

Earlier, on the 20 September, The Times records the influence of the mock action that Hope Grant’s forces had on the landscape, and wider vistas available to spectators:

The knolls and spurs on Bagshot-heath, facing the enemy, were converted into earthworks with emplacements for guns, lines of epaulement or trenches in some instances connecting them, and following the profile of the ridges, but the time and means at their disposal did not permit the Engineers to intrench the front completely. Staples Hill was turned into a small redoubt, with three lines of trenches for riflemen, one above the other, below the guns, and fortified with sandbag parapets, and it crossed its fire with that of works on the flank, something of the same kind; but one critic objected to the horses and ammunition of the guns being placed inside one of the square redoubts, as it may be called, and another thought the parallel lines of the rifles trench round Staples Hill a mistake, on account of the loss to which riflemen on the face of the hill would be exposed from the artillery fire directed against the guns from just above. But any way Sir Hope Grant’s inner line presented a very hard nut to crack, and when the enemy turned his left flank they found their front before a strong position defended by earthworks, and their line of advance enfiladed from the guns of the works, the defending force having by that time retired within a V shaped line of which the end of the V was Staples Hill, flanked by Fox Hill. It will be seen that there is not much variety in local nomenclature…Escaping from the hedges and their dust-clouds we climb Pibs Down, and get a splendid view of the country. We are among Carey’s troops, already well to the fore. And here is one of his Batteries playing on a massed column of Horse Foot Guards ranked along the edge of a wood a mile and a half off. Fox Hills and Grant’s right Batteries are the same distance in front of us, and there could not be a better point from which to study the whole position. The ground is high, and country extending into several counties is spread out round us like a map. Beginning on the left at the Bagshot-road and the railway, and travelling towards the right, first come Fox Hills and their works, then Staples Hill and more Batteries, then Gracious Pond, behind which is the centre of the enemy’s position – a great square redoubt, and in the distance Flutter’s Hill, his left. But soldiers and guns and intrenchments are a very small part of what is seen from this commanding height. A great expanse of waste moorland, of wooded and cultivated country, a wide and beautiful landscape, lost at last in haze, but clearly spread out for many miles on every side, delights the eye…

Further descriptions were also written about :

The position of the defenders left them the roads to Staines and Windsor…The works, however, at Chobham-common were not finished, and up to the last moment this morning men were digging trenches as hard as they could dig. The position occupied by Sir Hope deserves more than a casual description. Looking at the map it will be seen that there is a road running out of Bagshot on the right of the London road, facing towards London, and passing through Windles Hamlet, across a ridge between Pibs Down and Wodlands, thence bearing to the left through Hyam, and from this across hill and valley almost in a direct line to Chertsey. Just beyond Hyam are the cross roads leading to the left Sunningdale Station and on the right to Pankhurst. A little further on is Fox-hill, which would be about the centre of the battle at its commencement this morning. Commencing with Fox Hill there are several others northwards as afar as the Wokingham Railway, which is deep cut in most places. Again to the west of this line is another composed of Pibs Down, Long Down, King’s Hill, and the old entrenchment. On Long Down alone of this line were there any earthworks. Here there was a redoubt which eventually fell into enemy’s hands. About threequarters of a mile to the east of Fox Hill is Steeples Hill, a wonderfully strong position, its highest point about the centre of its ridge, which is a quarter of a mile ling, running north and south. In the centre rise a precipitous mound, crowned with a clump of long, fare fir trees, which form a landmark for the surrounding country. This knoll

had been strongly fortified. On the top a redoubt, formed of four walls made with sand-bags and earth walls,, protected a strong force of cannon. Around its base were cover trenches in three terraces, formed by digging out about two feet of earth, and throwing it up wall fashion in front. These cover trenches extend away behind and to the next redoubt, about four hundred yards away direct north-west, and on what may be termed the plateau of Steeples Hill, and known as Birch Mill. This redoubt was a bout forty yards square and very strongly built, with a ditch all round, and surrounded again by cover trenches for infantry. Travelling then from here in a direction nearly at right angles to the railway cutting, which is about a mile, will be found two more hills, called Oyster Shell and Ship Hill, each connected by cover trenches. These three, and the one on Steeples Hill, commanded the valley in front, that at Steeples Hill and the one below it having two faces, west and east. At about right angles to this line was one running in an easterly direction, with two more redoubts of equal strength on Long Cross Hill and Lodge Bush Hill. All these were connected by cover trenches, and round the redoubts double lines. Forty pieces of cannon were distributed over the position, giving about a battery to each, some being 16-pounders. The net-work of trenches was wonderfully arranged, and the position had the advantage of being able to move guns to either flank of centre, without being the least degree uncovered.

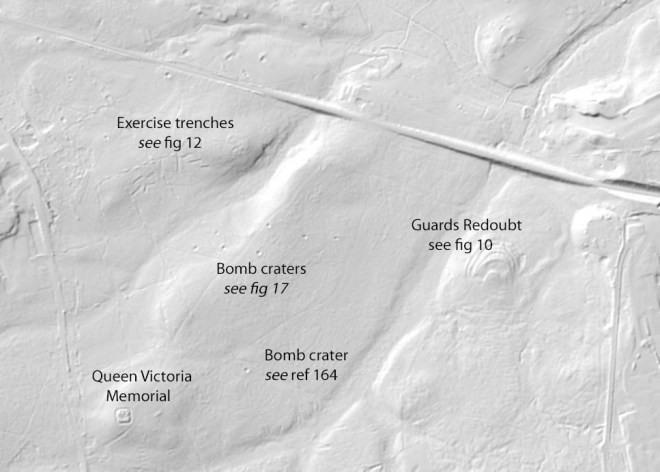

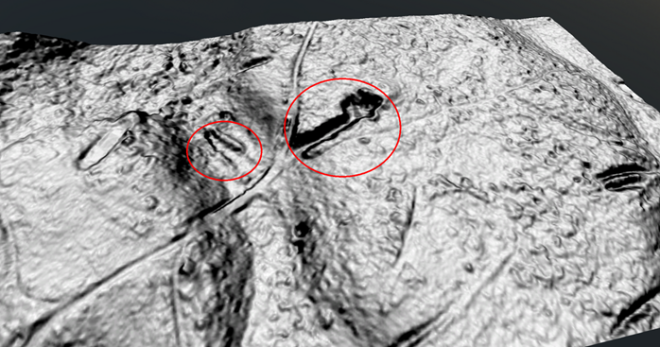

Although the 1871 Ordnance Survey map portrays ‘redoubts’ on the hills, the map accompanying the orders shows the “Battle of Chobham Common: operations on the 19th September 1871″ ‘defences’ in general (fig 7), it is James Wyle’s plan, published in the Illustrated London News , that gives the complete picture of the fortifications (fig 8). For a very brief fictional account of the “Battle of Chobham Common” see MALLINSON’s A regimental affair. Figure 9 illustrates part of WYLD’s plan overlain on a LiDAR * image.

* A remote sensing technology that measures distance by illuminating a target with a laser and analysing the reflected light

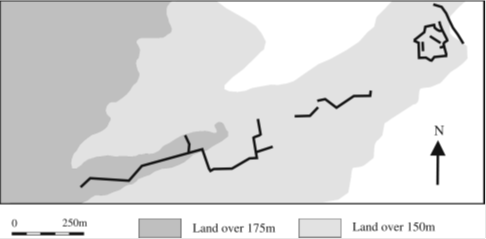

Figure 9 Part of WYLD’s plan of the 1871 earthworks overlain on the LIDAR

The Staples Hill redoubt in the above scenario was “…garrisoned by Middlesex Militia Regiments and Volunteers (seven battalions under Colonel Burnaby, Grenadier Guards)…” . This was illustrated by the following image:

Figure 7 Battle of Chobham Common

Figure 8 Plan of Sir Hope Grant’s Intrenchments on Chobham Common

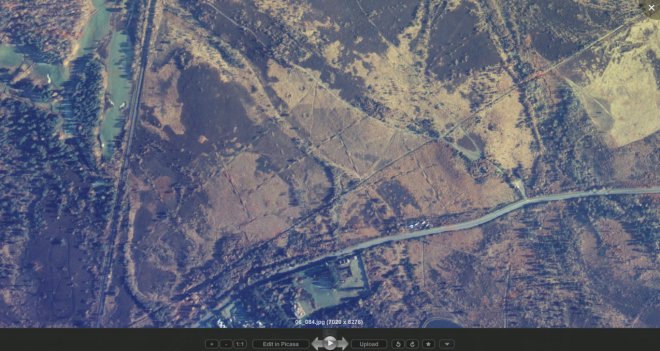

To the northeast, the Guards Redoubt (as named on Wyld’s plan) has characteristics of an Iron Age fort (figs 10 and 11).

Figure 10 LIDAR image of ‘Guards Redoubt’

Figure 11 Google Earth image of the Guards Redoubt (date September 2014)

Others have been similarly been fooled – an ‘Iron Age fort’ that is the remains of a redoubt:

In medieval and later periods the heathlands of south-east England were marginal in agricultural and settlement terms although, as manorial waste, they offered a range of resources that were exploited according to the customs of individual manors. Later, unenclosed heath provided an opportunity to obtain a small plot through encroachment and during the late 18th and early 19th centuries small squatter communities developed on the sandy heaths between Farnham and Aldershot and elsewhere. However, recognition of the need for a permanent military training area led to the purchase by the Government of large areas of heath and the settlements were expunged. On Sandy Hill and Hungry Hill a series of earthworks, once considered prehistoric in origin … have more recently been identified as 19th century in date and military in origin…

Military earthworks derived from late 19th century OS maps; the redoubt surveyed on Hungry Hill is that on the eastern end of the ridge.

A description of a 19th century redoubt reads similar to the plan of the ‘NE’ redoubt on the Common:

The redoubt proper, in which sat the battery, was a natural, elongated mound the size of a frigate, fortified by gabions and stonework [not in the case of that on Chobham Common], the embrasures revetted with logs, but the surrounding trenches were dug only three feet down, with breastworks of four feet built up from trench spoil and that from the dry moat which circled the whole redoubt…

To reinforce the composition of the redoubts themselves, The Week’s News records the following :

His right rested on King’s Hill, and extended along the summits of a series of low eminences to Lodge Bush Hill, on the east of the road between Chobham and Long Cross. He had fortified each summit and minor summit of these eminences, and had connected the whole by a continuous shelter trench, while the front was densely studded with rifle pits. The positions of the field works were singularly commanding; the ground before them was like a natural glacis, only of double the depth of any glacis. Reckoning from his right (west) he had first, in his “Life-Guards” Battery, three 16 lb. guns; next, in his “Life Guards” Redoubt, three 12 lb. guns; next, in his Flagstaff Battery, a battery (six guns) of 12 lb. guns; next, in his “Oyster-shell” right redoubt, three guns; in his “Oyster-shell” left redoubt, the apex of his position, four guns; next, in his “Staples Hill” right redoubt, three guns; in his “Staples Hill” Sandbag Battery, two guns; in his “Staples Hill” left redoubt, three guns; in his “Lodge Bush” right battery, three guns; in his “Lodge Bush” left brigade, four guns. In all, including those of his Horse Artillery, the defender had forty-two guns against thirty-six of the invading force, six of which were detached with the Horse Artillery.

After these ‘formal’ manoeuvres, military activity continued on the Common in subsequent years. In March 1876 the War Office applied to the Secretary of the [Chobham Common] Commoners’ Committee, Mr William M Medhurst, to hold Field Days for the 1st Buckinghamshire Rifle Volunteer Corps . Later that year the Secretary of War even contemplated purchasing parts of the Common for military manoeuvres . In November 1877 part of Chobham Common was purchased by “H.M.’s Principal Secretary of State for the War Department” and in the Spring of 1879 receipt from the Inclosure Commission for £150 10 6d was received in compensation for lands on Chobham Common purchased by the War Department.

The Common was continuing to be used for military activities as the General Office Commanding, “Army Corps Camp, Chobham Common” was reminded by the Commoners’ Committee that the Army would “…be held responsible for any damage which may be occasioned to the herbage” . In July 1889, the Commoners’ were warned that a Field Column “…probably the week 16th July for one night” would be camping . The following is an account of a night march and successful attack by one battalion on the camp (19 July 1889):

An advanced force had been sent from the Army Corps of the Invading Army at Aldershot, to Cowshot Manor, upon the 17th, as stated in the general idea. A battalion from this force marched in accordance with the instructions contained in special idea… at 8.15 p.m., towards Chobham. Very great care had been taken by the commanding officer to carry out the orders to reconnoitre the enemy’s camp, and to ascertain the position of his outposts.

The reconnoitring officers became subsequently the scouts and guides of the column. The column first halted three-quarters of a mile south of Chobham, in consequence of a report that a vedette was posted upon the bridge, over the Hale Bourne, upon the north end of the town, the reliefs being more than a quarter of a mile behind. After some delay, this vedette, who had dismounted and was smoking, was surprised and captured by the attackers. The Cossack post to which the vedette belonged was placed at too great a distance to the rear to render assistance. The non-commissioned officers, however, sent a verbal warning to the camp of the impending attack, but the trooper lost his way.

The column immediately upon this passed through Chobham, and having dropped parties to clear all approaches and also to cover the retreat, turned to the eastward and directed its march with the most complete silence and regularity upon the southeastern extremity of Chobham Common. The column reaching this point at 12.20 a.m., was brought to a halt by a signal from the scouting officer, that a vedette was in the vicinity. In a moment the whole column halted, and sank silently into the heather. The vedette nevertheless challenged, and not being answered, galloped back to his post, which eventually warned the general in command, of approaching danger.

The column continued its advance, and turning northward, crossed the deep bog at Gracious Pond by a narrow path- the only possible passage. By 12.45 a.m. the column arrived 600 yards south-east of Staples Hill, and leaving the shelter of a dark fringe of trees, which had been followed for a considerable distance, it formed up in quarter column.

Bugle sounds were heard in camp, and it appeared as if the enemy was on the alert.

The scouting and reconnoitring officers now led the column direct towards the key of the enemy’s position. viz: Staples Hill. Which, visible against the skyline, made a very favourable objective. Silently and with great rapidity the column advanced up the hill, till, favoured by the slight haze, it closed upon the very centre of the camp and halted in front of the tents at 12.55 a.m. without any opposition.

The Umpire-in-Chief having considered the different accounts makes the following remarks: –

…The bog near Gracious Pond, distance 1,800 yards, seems to have been assumed to be an impassable obstacle, but there is one good pass, by which the invading force crossed…

Lord Onslow had authorised the Adjutant General’s office in Aldershot to hold “…encampment and manoeuvres…” in the first week in July 1890 , although in early 1893 the Commoners’ were complaining again of the damage to the Common by exercises . It also seems likely that the Common was a popular place to hold annual summer camps under canvas for volunteer units (for example, units to which the later Royal Army Medical Corps (Volunteers) were attached). Some exercises were cancelled after permission had been given; in September 1896 a letter was sent to Lord ONSLOW saying “wet weather” meant a unit was unable to get onto the Common.

1900-1920

In July 1900 E A DOWNHAM visited and examined an earthwork on Oystershell Hill. He drew a plan (at 25 inches to the mile) but has no points of reference other than the description that it was a “…small enclosure [that] stands upon unenclosed pasture land some 175 feet above sea level with the ground rising toward the S. to 227 ft ½ a mile distant”. He then refers to earlier Ordnance Survey maps and their description of the feature as “Battery”. DOWNMAN records that the “entrenchments are not in a good state of preservation” . Interestingly, again, he records that the Bee Garden (“…½ a mile S.E.”) is shown on the OS 1880 map as “Battery” but that he “could find no such work…”

Military training was still taking place although some Army units had been refused permission to train on Chobham Common. James REMNANT, MP for Finsbury Holborn tabled the following (with the answer) on 3 August 1903:

To ask the Secretary of State for War whether he is aware that the 3rd Company of London Imperial Yeomanry, which is at present undergoing its annual training at Chobham, has been forbidden to manœuvre on Chobham Common; and, if so, will he state the reason for such prohibition.

(Answered by Mr. Secretary Brodrick.) This company has been refused permission to manœuvre on Chobham Common, but I am not aware of the reasons for the refusal. It has, however, been granted permission to manœuvre in Windsor Park.

In 1907, the War Office was raising the possibility of regularly using the Common (there are images of military vehicles passing through the village of Chobham captioned ‘Army Manoeuvres 1907’). It reflected ONSLOW’s concerns that the public might “flock” to such events and urging him to meet with General Sir Frederick STOPFORD, at that time General Officer Commanding, London District.

Although barely documented, it would seem that in the early part of the 1910 decade, Chobham Common was used for gravel extraction:

A dispute has arisen between the Chertsey Rural District Council and the War Office with respect to the right of the former to take gravel from Chobham Common for the repair of the roads in the neighbourhood.

Leading up to the First World War, Chobham Common was used for field days by amongst others Radley College, Oxford’s Officer Training Corps (OTC) who appear to have held “private days” with Eton.

On the outset of war, the Common was being prepared for early prisoners of war. A newspaper report of September 1914 referred to Chobham Common West End as being prepared for enemy prisoners. The Common also was, as previous generations of soldiers found good ground for training for war, obviously familiar to those who fought at Gallipoli (April 1915) if this quote is anything to go by:

Faint clouds of dust, through which may be seen the glistening of steel and dark masses of uniform, blur the landscape here and there, and betray the march of troops along the sandy roads, which are exactly like those worn by the tramp of men and horses through Chobham-common, and have neither fence, boundary, metal, nor drainage.

The local newly-formed Surrey Volunteer Training Corps (VTC) took the opportunity of using the Common for field days. The one held in late May 1915 by the 3rd Surrey VTC consisted of the Chertsey and Egham Companies acting as an ‘attacking force’ on Staple Hill, which was defended by the Weybridge and Addlestone Companies (the individual companies had held an earlier training day in April 1915). The report on the exercise noted that:

…Scouts were at once sent out over the ridges in the direction of Ottershaw to try and ascertain the enemy, whose presence in front was quickly signalled, and battle was joined. It was awkward country over which the attacking party advanced and popular sergeant, in leading enthusiastically, found himself nearly waist deep in bog and water. When operations closed, honours were easy, although the Weybridge Company seemed to hold points in the game by a somewhat conspicuous display of “prisoners”…

However, it seems natural that with the need to practice trench warfare, troops barracked at Woking, Pirbright and Aldershot would use the ‘wild’ Chobham Common. Systematic exercises were carried out in August 1915; a scheme involving the whole of the 24th Division (as part of Kitchener’s New Third Army – K3) was mounted on the Common when it was intended “…that the troops should occupy trenches for several days with regular relies throughout and a trench-to-trench attack at the end of the exercise.” The 24th Division was one of a group that was being held in reserve for offensive operations, so they did not go abroad immediately; “…within a few weeks, the inexperienced division was thrown into action at Loos and suffered appalling casualties”. The intervening period saw training at Chobham Common in trench construction and trench attack and was carried out under active service conditions. The 8th Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment as part of the Division was inspected by Lord Kitchener on 19 August 1915 (followed the next day by King George V ,):

The rest of the month of August was devoted to training in trench warfare, final preparations for proceeding overseas, and embarkation leave. The trench-warfare scheme was carried out by the whole division. The two opposing forces marched under war conditions until they met on Chobham Common after dark, when each side commenced to dig in with entrenching tools until the large tools were brought up. Work was continued under war conditions until 7 o’clock the next morning, when peace conditions were resumed in order to enable the work of completing the trenches to be pushed on more quickly. It was intended that the troops should occupy the trenches for some days and that reliefs should be practised, and finally a trench– to-trench attack and consolidation carried out. It happened, however, that the weather was very bad, and the scheme was abandoned on the second day.

On that day the King and Queen visited the Division and walked along the trenches, speaking to many of the officers and men, and we felt that this foreshadowed a fairly imminent departure for other trenches. Immediately the trench-warfare scheme was abandoned, embarkation leave commenced, each man getting four clear days.

On about Wednesday, August 25, instructions were received to be ready to proceed overseas on the following Sunday…

The trenches the men dug bore little resemblance to those they had dug elsewhere by some units (eg 7th Northant’s at Shoreham or Southwick ) and the units benefited from the extra weeks training. It happened, however, as recorded above “…that the weather was very bad, and the scheme was abandoned on the second day”

On 24 August 1915 H.M. King George V with H.M. Queen Mary and H.R.H. Princess Mary inspected the 24th Division while working on trenches, and passed along the trenches held by the 13th Middlesex .

Transcribed War Diaries of the 12 Bn. Royal Fusiliers by 2nd Lt (later Capt) J V Wilson record some of this trenching activity:

Box Brownie photographs were also taken of entrenching activities, presumably between 23 and 26 August 1915 (see PDF for photographs) .

The Bedfordshire Regiment were also on the Common:”…23 Aug 1915 – Chobham Common…Battalion carrying out Trench Warfare on CHOBHAM COMMON.”; as were 2/6th (Rifle) Battalion, “The King’s” Liverpool Regiment.

The trenches can be seen in Figure 12, north of the Memorial, and in figure 13 south of Staples Hill.

It would interesting to compare the layout and profile of the what remains to the contemporary instruction on trench digging:

After the War, the Army continued to make use of the Common, on the doorstop as it was with Aldershot and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. The Common was still the property of 4th Earl of Onslow, and permission was required as seen in the following request in 1929 from Lt Col G GLOVER, Command HQ Aldershot:

It is very kind of Lord Onslow to allow the 1st Bn. Royal Ulster Rifles, to use the Common. A bivouac only consists of the Company sleeting part of the night under waterproof sheet shelters. No fires need to be lit as the company will be issued that no trenches are to be dug, fires lit, or brushwood cut.

It is probably desirable for sanitary reasons that some shallow pits should be dug for latrines. There will be as few as possible and will be filled in.

Figure 12 LIDAR image (The Memorial – bottom centre/left) Note: the Second World War bomb craters centre right (see later)

Figure 13 LIDAR image (Staples Hill is top centre) Note: bottom centre/left shows the Bee Garden (see above)

Additionally, the Common was also being used by the Army Staff College at Camberley in June 1915 for TEWTS [Tactical Exercises Without Troops] (see the account in WARNER).

As today, fire was a hazard on Chobham Common and a number were reported in May 1917 exacerbated by “abnormally dry weather” with soldiers being used to help bring them under control. The newspaper article highlighted the dangers of numbers of blank cartridges lying around and “small bombs” dropped by practicing airmen – inferring that the Common was used for aerial bombing practice.

A letter dated August 1919 indicates that sand was being extracted by the Burrow Hill Silica Works with first a kiln then later a “drying machine”.

1920s-1939

In 1924, T M NEWELL, Engineer-in-Chief of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board requested of Lord ONSLOW the extraction of 8-10 tons of sand by Messrs Stearn & Sons, “Heathfield”, Sunningdale for the maintenance of the channel of the Port of Liverpool. The proposal, which seems to have been accepted, was the “…removal of the sand and the filling up of the area [?Longcross Farm area?] and replacing the turf, no greater depth than 6 inches was to be removed at any one place…” over a 20ft x 20ft plot. They were prepared to pay 10s per ton for the sand.

From the late 1920s the Chobham Common Preservation Committee was responsible for the management of the Common on behalf of Lord ONSLOW.

However, concern was mounting on the future of the Surrey Commons as witnessed by part of the question from Earl Russell in the House of Lords in November 1927:

I hope to elucidate, if I can, from the noble Earl opposite (the Earl of Onslow) what the real intentions of the War Office are with regard to the commons in Surrey and places near London. Your Lordships are no doubt aware that this question excites a great deal of interest and, I think I may fairly add, a great deal of apprehension, because there is a feeling that the attitude of the War Office is a little like the attitude of the wolf to Red Riding Hood. People who use and who live near these commons are rather afraid that the commons may be swallowed up and cease to be available for purposes of public recreation…. He will, no doubt, be able to give your Lordships many more concrete facts than I can give. I have endeavoured by reading what has appeared in the public Press and in particular what took place when a deputation visited the War Office, to find out exactly what it is the War Office desire to do. As I understand, it is said that this open space is required for the purposes of manœuvring, chiefly, I think I am right in saying, what is called the new mechanical Army…. [The Earl of ONSLOW: Not chiefly]…Well, partly at any rate, the new mechanical transport. In that connection a demonstration was given by the War Office which was very fully reported, the other day, in which some tanks appeared to have behaved very respectably on hard ground under observation and as a result of which, for one moment, I was afraid the noble Earl opposite (the Earl of Midleton) had been squared by the War Office; but I hope your Lordships will find to-day that that is not so. It was reported that one unfortunate incident took place. A tank was asked to pivot and I think The Times, in describing what took place, made use of the words “disastrous in its results,” by which I suppose The Times meant that the tank did completely turn up and destroy the ground round about it. I was not there, but I gather that was what was meant. First of all, no doubt the noble Earl, Lord Onslow, will tell the House why this extension of the War Office powers is necessary, why new powers and new land are necessary for their operations beyond what has sufficed in past years. Secondly, he may be able, though I doubt it, to reassure your Lordships and, what is more important in this connection, the general public as to whether in fact these commons will remain available as places of recreation.

In the ensuing response from the Earl of MIDDLETON (who had held various ministerial posts in the War Office), he highlighted, in response of an intervention by the Earl of ONSLOW (who at this point was the Under-Secretary of State for War) that Chobham Common was his land, that when in post:

…it was ruled for me that, though the Act of 1842 was available when the War Office wanted to take sites for ordnance for the defence of the country, it was not available when the War Office wanted to take sites for manœuvring. At the beginning of the War, when the War Office seized upon this common, I went to the officer in charge on the spot and asked: “Under what Statute is this done? I am ready to give up anything to the War Office, but I should like to know under what Statute it is being done.” He said: “I admit that under the Statute we cannot do it.” But he turned over a page and said: “Under the Defence of the Realm Act anybody who obstructs the Commanding Officer may be removed from the district. Therefore I am afraid you will have a very poor time if you object.” I admit that that was a very proper course in the circumstances.

In replying to the question, the Earl of ONSLOW reported on the period of training on the Commons:

From March to May squadron, battery and company training takes place, when the troops train close to barracks. June and July are the training periods for Cavalry regiments, Artillery brigades, Infantry battalions and brigades. That is the time when it would be most necessary to have a change of area, and when the commons would be most useful. In August the areas are very little used, as the troops are engaged in shooting, and there is not much training done. In September the Aldershot troops are as a rule absent in other training areas. That is the time for divisional and inter-divisional training, and they would probably be away. In winter there is no training of troops, but parties of officers and non-commissioned officers carry out tactical training without troops.

He went on the explain that a Committee [name unknown] had been established “…representing all the interests, the landlords’ interest, the lords of the manor, various public bodies, like the National Trust, and the War Office” under the chair of the Earl of MIDLETON to consider the use of the Commons. It was still deliberating but the Earl of ONSLOW was able to report that:

…in general words that we are prepared to enter into suitable covenants to use the commons in such a manner as will not destroy their natural amenities, not to cut down trees, not to dig permanent trenches, not to erect buildings other than temporary shelters, and to give the public access to the commons when they are not being used for military purposes.

He then went on to state:

It is true my father sold a small portion of Chobham Common. I wish he had sold the whole; but he did not, and at present the arrangement is that the Brigade of Guards go there and use the common. I asked my noble friend, who is not in his place at the present moment, whether he had used vehicles there, but he has not, so I cannot speak as to that. I dare say many of your Lordships are familiar with Chobham Common. Except at Queen’s Clump, there are practically no trees, and it is mostly open heather, so that, of course, the question of trees does not arise. But there is the question of fire, which was referred to by my noble friend behind me. I have several other commons round Chobham, and we have a great deal of trouble with fires, but I can safely say that, when fires do occur, it is not the fault of the troops, and I would very much rather that fires occurred on Chobham Common when the troops are there than when they are not, because they break off what they are doing and set to work to beat out the fires. It is part of the arrangement. So the enormous numbers of troops on Chobham Common—I am speaking from my own experience—are far less dangerous than the mildest-looking nurses and children, especially at tea-time. As far as fires are concerned, the troops are an advantage rather than a disadvantage.

Towards the conclusion of the debate, the Earl of ONSLOW stated:

…that there must be an extended area for such [Army] training. What happens is that the Island is small and people want to use more parts of it than they did before. The alternative to utilising the commons is that we must either not train the Army—and I think nobody would suggest that—or we must utilise common land or buy agricultural land. Those are the only three alternatives, and I think the utilisation of common land is probably the least expensive.[Earl of MIDLETON: The right to buy common land?]… The right to go on it. I do not think I ever suggested anything more than that right.

So the Army continued to make use of the Common, on the doorstop as it was with Aldershot and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. In late 1927 Aldershot requested permission to train from 1 March to 30 September 1928, including tanks. There was, this time, a resounding ‘No!’. The Common was still the property of 4th Earl of ONSLOW, and permission was required as seen in the following request in February 1929 from Lt Col G GLOVER, Command HQ Aldershot:

It is very kind of Lord ONSLOW to allow the 1st Bn. Royal Ulster Rifles, to use the Common [ 16/17 May 1929]. A bivouac only consists of the Company sleeting part of the night under waterproof sheet shelters. No fires need to be lit as the company will be issued that no trenches are to be dug, fires lit, or brushwood cut…It is probably desirable for sanitary reasons that some shallow pits should be dug for latrines. There will be as few as possible and will be filled in.

This particular request, however, was the start of some acrimonious correspondence between the Army and Lord ONSLOW and his representatives on the military use of the Common. Initial, the idea of bivouacking caused horror from the latter prompting Maj Gen Charles CORKAN, General Officer Commanding to send a placating letter dated 28 February 1929 assuring ONSLOW etc that Standing Orders set out what was allowable on the Common (see PDF for figure 14).

This, however, caused ONSLOW to give on 3 Mar 1929 formal notice to terminate on 1 July 1929 the arrangement with HQ London District. On 21 March 1929, ONSLOW amplified this arrangement by writing:

…anybody wants to use Chobham Common it should be with my permission. The London District have general permission and don’t need to ask whenever they want to go…

What had upset Lord ONSLOW was that HQ London District has themselves been given permission to other units not in London District to exercise and train on Chobham Common. ONSLOW suggested that the War Office should come to some more satisfactory arrangements. What those arrangement were is so far unknown as the Army continued using Chobham Common for training – the following shows the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards undergoing training on the Common in 1934.

In May 1936, Lord ONSLOW’s agent received a request to extract sand from the Common at the rate of 100 cubic yards per day. His advice to ONSLOW was that the Chobham Common Preservation Committee were likely to object and that there should be a delay in making a decision.

On 13 May 1936 their meeting reported that “…the Army had done considerable damage to the common with their vehicles…”.. The Committee also agreed to construct two carparks – Staple Hill and at the Queen’s Memorial – both bounded by ditches. On 12 June 1936 it is reported that “…G.O.C. Aldershot were sending out a representative to talk to Sir Edward [Le Marchant] re: damage done by the troops.” . On 2 Nov 1936 it was reported to the Committee that:

Major General Commanding London District had written seeking permission for O.T.C. contingent of Imperial Service College and Beaumont College to hold tactical exercises on Chobham Common on the 12th November and to use blank ammunition during the exercise. This was granted.

The Committee agreed to grant permission for the Whitgift 0.J.C.[sic] to hold exercises on the Common

On 9 August 1937 it was reported that there had been”…Damage to the Common by the Bat. of the Coldstreams. The Chairman had been visited by Major Sands, the Compensation Officer of the Aldershot Command” . In December 1938 it was agreed to repair “…damage done by military to trenches etc” . Also by the 1938 it is recorded that there was much correspondence between Lord ONSLOW and the Army over the Army’s use of the Common “…for training purposes [and] the digging of defensive ditches…”.

In their report for 1937, Chobham Common Preservation Committee noted that Scotch Pines [sic] had been planted at the northern end of Oystershell Hill in celebration of King George VI; permission had been given tio various schiolls to have field days on the Common; and that the “…Fish Pond (Dunstall Green)…” had been cleared of 40+ years of silting.

On 25 July 1938 it was reported that:

The Secretary reported that he had received a new agreement between Lord Onslow and the War Office from June 1939 for ten years. Mr. Acworth also referred the damage which was being caused by army lorries to the ditches which had been cut for the protection of the Common. Mr. Acworth had written complaining to the O.C. Pirbright and had suggested that parties should be sent at regular intervals to repair said damage. Sir Edward Le Marchant thought it would be better to get the War Office to send down their Compensation Officer to assess the damage.

By December 1938 “Major Saunders, the Compensation Officer from Aldershot, had agreed to repair the damage done by the military to trenches, etc…” . In May 1939 it was reported that the Committee discussed “…whether War Office needed more facilities. Mr. Acworth explained that under the Manoeuvres Act of June 18th, apart from now being able to use heavy 17 ton lorries, the standing agreement with Lord Onslow and the War Office was extended to September 18th…”

1939-present

Later activities on the Common can be related to the Second World War and immediate post-War. Just off Chobham Common (for the purposes of this study), to the north-west of the roundabout on the B383/B386 LIDAR images (fig 15) show square ‘structures’ and the belief is that it was a prisoner of war camp:

There had been an Army Camp, on the left hand side going to Sunningdale. There were many camps, an Army Camp, going down to Brickhill called Valley Camp, a prisoner of war camp – mostly Italians – over near the tank factory, built about 1938/39

Figure 15. LIDAR image showing camp ‘structures

But what was the camp? Local knowledge call it a camp for Canadians:

…My husband lived in Brick Hill all during the last war. He well remembers the POW camp and then the “Squatters”. Prior to it being a pow camp, serving soldiers, mainly Canadians, were stationed there. The local women would do their washing in exchange for sweets, cigarettes and money. Many left one night never to come back they were killed during the D day landings….

My father was Canadian soldier stationed on the common. Back in early 1970 he showed me where his motor transport garage was sited. This was very close to the roundabout…

…for Germans:

…Accommodation was in very short supply, and living with relatives was the only solution. We heard that the tin Nissen huts at Chobham Common were being rented out by Bagshot Rural District Council for 8/6d…There were still German prisoners of war in some of the huts, safely wired off in a separate compound…

My Dad was in a Panzer regiment and ended up at the Chobham camp by way of repatriation. He was on a train from Liverpool bound for Hull to be put on a ship home. The Russians started doing their thing and the train was diverted to Kempton race course. From there he went to the Chobham camp. Like lots of other POWs (there were Italians as well as Germans) they worked at Hillings along the Bagshot road.

…or Italians – although camps at Ascot and Old Dean seem to have been sites for possible PoW camps for this nationality .

More definite are the bomb craters on the Common. Chobham Museum has on display, on a wall, a map of Bagshot Rural District Council (ca 1925) with sites of bombs (figure 16). Interestingly, there seem to be more bomb craters plotted from the 1948 air photography and LIDAR (although this could be a positioning error) (figure 17). Against the plotted bomb sites on the map are pencilled dates; unfortunately some of the dates are meaningless (eg “23/25/40”), however, the bombs dropped over Albury Bottom are marked “11th September, and a group of bombs in Sunningdale, marked “9/9/40”:

I was born into a large family in Sunningdale. I well remember bombs falling on Sunningdale…German bombers used to come over and target the town…

Figure 16. Copy of map with Bomb craters plotted

Figure 17. Previous image with Chobham Museum’s map as an overlay (to compare its plotted bombs with what can be seen on images)

The Surrey History Centre (SHC) has plotted the bombs and other munitions dropped on Surrey and this shows a stick of four High Explosive bombs (HE) in a South West-North East line over Albury Bottom, confirming the map above. Eight HE and two incendiaries were dropped to the North West of Burnt Hill. According to the SHC, 13 HE and 2 incendiaries were dropped over an area of Little Arm, Long Arm and Ship Hill on the 23 May 1940.

The widely held belief in the Museum is that (a) they were targeting Sunningdale station, and/or (b) they were dropped during the Battle of Britain (July-October 1940) . Raids were extensive during the period; reporting in Woking started on 23 August 1940 on a bomb dropped at 0255 on Horsell Common – substantial reporting continued on a monthly basis, with bombs dropping for example, on Brooklands, Byfleet as well as extensive parts of Woking . Raids were reported, for example, between 1635-1730 and from 2000hrs on 9 September 1940, including bombs at 2225hrs on Sutton Green Common and at 2350hrs on Horsell Moor ; daylight raids were recorded between 1545 and 1645hrs, and later 2020-0530hrs on 11 September 1940 . There is a theory that the bombers were targeting the locally known ‘Tank Factory’ but that did not move to Longcross until 1942. It should also be noted that Heinkel He 111-3 (3322) of 6/KG26 (Luftwaffe) crashed on the recreation ground of West End on 24 September 1940; is there a connection with the bomb craters?

In 1942 the Department of Tank Design * at Farnborough spawned the Fighting Vehicles Proving Establishment (FVPE), which moved in the week 22nd-29th June 1942 “…to a new purpose-built camp in Chertsey on the site of the former RAF Chobham that was convenient for testing tanks on Chobham Heath. The School of Tank Technology (STT) (part of the Military College of Science) was also housed at Chobham – its first course ran in December 1942″. The Wheeled Vehicles Experimental Establishment (WVEE) was also formed out of the DTD in that year, and moved to Chertsey in 1943. In 1946 the DTD merged with WVEE to form the Fighting Vehicle Design Department (FVDD) at Chertsey alongside the FVPE. The FVDD was renamed the Fighting Vehicle Design Establishment (FVDE) in 1948. Four years later the FVPE and FVDE merge to create the Fighting Vehicles Research and Development Establishment (FVRDE).” Tank testing at what is known locally as the “Tank Factory” went on at the Longcross site into the 2000s (under various organisational names – Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment (MVEE); in 1984-5, the Vehicles Department of the Royal Armaments Research and Development Establishment (RARDE); RARDE was merged into the Defence Research Agency (DRA) in 1991; DRA then became a division of the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency in 1995; finally becoming part of the then partly privatised company Qinetiq in 2006 .

[* The Tank and Tracked Transport Experiment Establishment (TTTEE) was formed at Farnborough in 1925, which in turn spawned the Mechanical Warfare Experimental Establishment (MWEE) in 1928. The MWEE was renamed the Mechanisation Experimental Establishment (MEE) in 1934 and in 1940 the MEE merged with elements of the Design Department at Woolwich to form the Department of Tank Design.]

There are references to the Common being used as a tank training school , and the Imperial War Museum has photographs of Westminster Dragoons (2nd County of London Yeomanry)’s light tanks exercising on the Common on 6 August 1940 (see figure 18)**. In early 1942 David HOGAN recalls “…’When we were training [in the Royal Armoured Corps] we were on Crusaders and it was a lovely English tank…but we went onto American tanks and we did a bit of our training on Chobham Common in Sherman tanks’…”. The visit of Canadian Tactical School to STT on 23 October 1943 included demonstration of vehicles on the common that included “…Pz.Kw.III – Model L [and] Pz.Kw.III – Model J…”. There is also evidence that the Common was used for the evaluation of captured enemy armoured vehicles.

[** The Germans planted over four million mines along the French coast to hinder the Allied landings in 1944. To break through these defences at the start of the Normandy Invasion the British produced a number of novel armoured fighting vehicles under the ingenious direction of Major General Percy Hobart, including the Sherman Crab. The Crab bore a rotating drum with dozens of chains attached; these detonated mines in its path to produce a beaten passage through the thickest of minefields. Was it a coincidence that the Westminster Dragoons were trained in this vital task? They were the first units to land on Gold Beach on D-Day in the British sector clearing paths off the beach and using their tank guns to destroy defences holding up the assault (http://www.westminsterdragoons.co.uk/Westminster_Dragoons/Second_World_War.html )]

Figure 18. Westminster Dragoons exercising with Vickers Mk VI light tank (photographs from including Imperial War Museum)

The testing of tanks over the rough terrain of the Common had the greatest impact on the Common. Figure 19 – a composite 1945 aerial photograph – and figure 20 shows the extent to which tank testing covered the Common, notably trials involving mine-clearance tanks, such as those fitted with flails (see ** above).

Figure 19. Composite1945 aerial photograph of Chobham Common showing evidence of tank testing. See also individual photos in figure 19

Figure 20. Separate 1945 air photographs of Chobham Common.

The extent of these trials were such that major portions of the Common had to be ploughed and reseeded after the war . The Chobham Common Preservation spent several years after the War trying to get compensation from the War Office for the damage caused . Other testing took place at Chobham:

A Valentine bridgelayer with scissors bridge at the AFV proving establishment at Chobham in Surrey, 28 September 1943 (photograph Imperial War Museum)

Towards the end of World War II, designers were becoming concerned about the use of armoured vehicles over soft ground – vehicle trafficability:

The failure to find a suitable site for large-scale trials by January 1945 was a serious setback for the long-term research programme of the [Mud] Committee, which had to be put in abeyance due to the imperatives of war. Instead, the Committee turned its attention to the possibility of qualitative trials involving the use of an artificial ‘soil bath’ and other sites for comparative tests. The artificial soil bath was to be established at the FPVE at Chobham and would consist of a concrete lined bath 30m long, 9m wide and 1.8m deep me (100 x 30 x 6ft) with additional ramped ends 9m (30ft) long…This facility was not built and discussions were still in progress as late as 1946…However, a natural facility was made available at Albery [sic] Bottom on Chobham Common consisting of waterlogged loam, sand and clay with an underlying bed of firm clay.

Perhaps the following experience, of Lance Corporal Tony KING when seconded to the FVPE in 1944, is of the Albury Bottom ‘soil bath’ before the ‘Mud’ Committee deliberated!:

Chobham Common was used for cross country trials, including a most unpleasant “basin” of thick liquid mud and gravel through which tanks were driven slowly to test durability of things like bearings and oil seals. I recall driving a Valentine (Infantry Mark III tank, 17 tons) with a sharply raked-back front armour plate through this hazard, and watching apprehensively the evil smelling gunge lapping closer and closer to the open port in front of my face before the tank hauled itself out onto firm ground again.

Some of the tracks from these tests can be seen on a 1948 air photograph (fig 21). Later, such testing took place over a specially constructed track within the confines of the MOD estate. The Common was also used for special testing. Surrey’s HER records the existence of a ‘tank hide’ – see Appendix 1 – although William SUTTIE believes that “…in light of the large amount of testing and the need to drive to the hide I would not think it was dug for the specific purpose of hiding vehicles. More likely it was dug as part of tests of a tank with a dozer blade to see how long it took to dig what is a commonly used defensive position for tank” .

Figure 21. Air photograph (ca 1948) overlain on LIDAR image (examples of tank track bottom centre right) Note: rectilinear lines of WWI trenches

Demonstration also continued after the War; for example,in November 1948 the RAF Staff College visited FVDE and FVPE and their programme included:

Modern day features

So what can be seen of these features today? From the 1853 Great Camp, the most obvious is the redoubt near Victoria’s Memorial.

Ditch at Victoria Memorial

First World War trenches can still be seen to the north of the Memorial and on the south of the Common, between Staple Hill and Albury Bottom:

First World War trenches north of the Memorial

First World War between Staple Hill and Albury Bottom

Second World War bomb craters are still visible.

Bomb crater on Ship Hill

Further back the evidence becomes less distinctive, or non-existent (!). The earthworks below Guards Redoubt (see above) are prominent (and not ‘Linear earthworks, Long Arm’ as described in the Historical Environment Record reference SHHER_17490 – see Appendix 1):

Part of the earthworks around ‘Guards Redoubt’

Other earthworks created for the 1871 Autumn Manoeuvres around Oystershell Hill are recorded on Surrey’ Historical Environment Record (HER) – Appendix 1 – although evidence on the ground is dubious!

Enclosure, Oyster Hill (SHHER_3686)

Earthworks, possible enclosure unknown date: Oystershell Hill (SHHER_4679)

There is some evidence (albeit brief) that the Bee Garden below Staples Hill is military in nature . As for the other lumps and bumps…and the unexplained?

Surrey Wildlife Trust had asked volunteers to help excavate “mysterious” concrete structures on Chobham Common

Concrete structures (grid ref SU971644); structure in above photograph can be seen top right)

‘Western’ ‘tank hide’ – see Appendix 1

‘Eastern’ ‘tank hide’ – see Appendix 1

The following aerial photographs, taken in November 1988, clearly show not only the First World War practice trenches – beyond the Memorial in the first photograph, and in Albury Bottom in the second – but also the Second World War bomb craters (second photograph) and the rectilinear line of the ‘soil bath’ for the Second World War ‘Mud Committee’ (also the second photograph)

Many of these features are now becoming ‘visible’ through the use of LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). The Surrey Lidar Portal (https://surreylidar.org.uk/wp_sur/wp/ ) has enabled many of the feature described above – and more! – to be seen. This is an example:

APPENDIX 1

ENTRIES IN THE SURREY HISTORICAL ENVIRONMENT RECORD (HER) FOR CHOBHAM COMMON POSSIBLY RELATING TO MILITARY EARTHWORKS

As at 16 Feb 2015

(LIDAR screenshoots, with acknowledgement to James RUTTER, GIS Manager, Surrey Heath Borough Council)

Reference Number: SHHER_4728

Site Name: Possible earthwork at Long Arm, Chobham

Grid Reference: 497100 165600

Description: Long Arm. At the west end, on the sheltered northwest aspect, is a house platform and associated features linked by walling with some evidence of cultivation. There is disturbed ground with a mound evidently the result of earth-moving to east. Possibly a farmstead. A subsequent site visit in 2002 failed to locate this earthwork and therefore could not verify whether there is an archaeological feature at this site or not.

Long Arm is the channel running left to right (which is north to south) in this image.

Long Arm is the channel running left to right (which is north to south) in this image.

Reference Number: SHHER_17490

Site Name: Linear earthworks: Long Arm

Grid Reference: 497370 165980

Description: A series of linear terraces or banks can be seen following around the west side of a hill overlooking Long Arm valley. On top of the hill is a flattened area, with a remnant mound on the east side. The latter is either a spoil mound or a surviving remnant of the original hilltop, it being dug away elsewhere. Local tradition ascribes it as a tank hide, which is another possibility.

The linear lines around the west side of the hill have the appearance of linear ridges formed by quarrying on other commons in West Surrey (Ockham, Wisley, Puttenham). The only difference here being they cut into the side of the hill, giving them an unusual appearance that could be superficially mistaken for plough lynchets (which they are not). It is not impossible that they might be some sort of military trenching system built to defend the west side of the hill during army training in the 19th or 20th centuries.

Reference Number: SHHER_17491

Site Name: Tank Hide: Long Arm

Grid Reference: 497120 165470

Description: A short linear earthwork being an open ended hollow, with banks around the other three sides. The entrance to the linear hollow is on the north or east side (bearings were uncertain). The hollow itself is about 4m wide and about 20m in length. It is uncertain if it has been excavated into a hillside or if one side has been thrown up artificially to create a position where tanks could be hidden. Local tradition ascribes this feature as a tank hide. The dimensions and locations make this plausible.

Reference Number: SHHER_17488

Site Name: Possible battery: Oyster Hill

Grid Reference: 497290 165330

Description: OS 6 map of 1870 shows an earthwork enclosure here marked Battery (For Military Practice). Possibly erected during the Great Army Encampment of 1853. Site of sub-circular military battery, similar in shape and form to that on site of the Memorial Cross, which this one faces across Long Arm. The fact that they can be seen from each other across a prominent valley suggests they are contemporary. The earthworks were not seen when visited in January 2002 as the site was overgrown by gorse and the author was then not aware of its possible presence. It is shown on the 1871 OS 6″ plan (sheet 10), where it is marked as ‘Battery For Military Practice. It is shown again in 1898, but not on maps thereafter. Maps show sub-circular enclosure about 25m across, possibly surrounded by ditch.

A profile across the feature (the yellow line below the graph shows the profile measurement)

Reference Number: SHHER_4703

Site Name: Earthwork of unknown date, possible circular enclosure,

Grid Reference: 497200 165300

Description: North of Oystershell Hill, the local summit of the plateau on this side of the M3 features a possible circular enclosure, diameter 60 metres. On northwest-north there is evidence of a bank 6 to 8 metres spread, which at its highest appears as a mutilated mound about 1.5 metres high from the outside. Gorse and scrub obscures much of the site, but these is little more to indicate the inside perimeter of an enclosure. However the outer perimeter is very distinct on the north, east and south. Only on the southwest and west is it indefinite and confused. The interior rises slightly and has been dug and pitted.

Reference Number: SHHER_3686

Site Name: Enclosure, Oyster Hill

Grid Reference: 497200 165200

Description: A plan of an earthwork enclosure drawn at a scale of 25 inches to 1 mile, by Mr Edward Andrew Downman of Laindon, Essex between 1889 and 1905. Now in Kingston Museum ref. S(913) no.3666.

Reference Number: SHHER_4679

Site Name: Earthworks, possible enclosure unknown date: Oystershell Hill

Grid Reference: 497100 165200

Description: Observation of remains of a small enclosure opening onto a hollow at the west end, situated at an angle on the plateau of Oystershell Hill, on a sub-rectangular low rise.